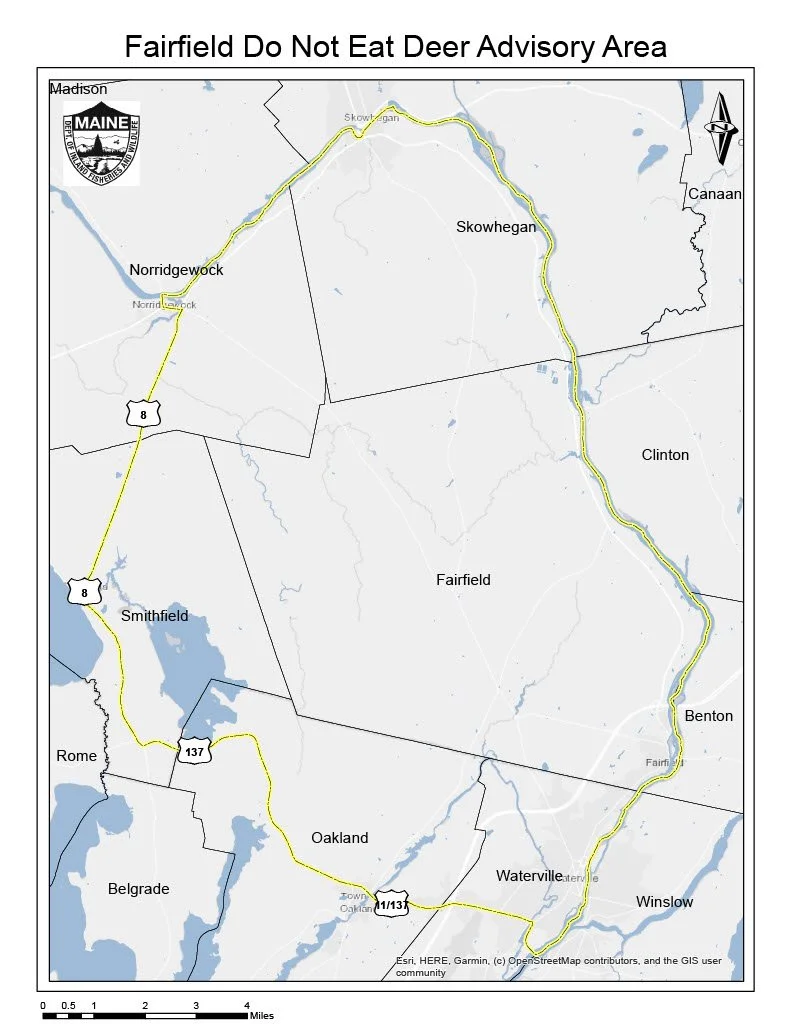

On November 23rd, the State of Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (DIFW) and the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Maine CDC) issued a Do Not Eat advisory for deer harvested in the area in and around the central Maine town of Fairfield (FairfieldAdvisoryArea.pdf (maine.gov)). The advisory was due to the discovery of relatively high levels (~40 ng/g or parts per billion (ppb) in 5 of 8 deer) of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), one of the most common of the per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). PFOS was measured in the meat and liver of deer that had foraged in the area of farm fields where soil and surface water is known to have high PFOS levels. Three of the deer tested from the same area had lower PFOS levels. According to the press release, there had been previous recommendations for reduced consumption of deer harvested in the area, but after consulting with the Maine CDC, the DIFW made it a Do Not Eat Advisory “out of an abundance of caution.”

Elevated levels of PFAS were first discovered in the Fairfield area during statewide sampling of milk after concerns were raised by the elevated levels of PFOS at the Stoneridge Farm in the southern Maine town of Arundel. The Arundel and Fairfield farms had both utilized biosolids and other residuals as soil amendments in the past, provided by wastewater treatment facilities that were not designed to remove these chemicals back when no one had even heard of PFAS.

It appears that, in both situations, there was some major industrial PFAS user(s) that caused very large levels of PFAS in their land-applied residuals. Because the Arundel farm is not allowing further investigation by the state, there is scant data with which to try to figure out what materials and what sources caused the high PFOS levels. In that situation, the local municipal biosolids that were used do not seem to have caused the issue, because the soil levels in fields that received only those biosolids have typical low levels of PFAS. In the case of the Fairfield farms, it appears there was a paper products manufacturer that discharged PFAS into one municipal wastewater treatment facility whose biosolids were routinely land applied in the late 1900s. The Fairfield farm is allowing further state testing and research, which has revealed relatively high levels of PFAS in additional soils, surface waters, and wells in the neighborhood.

Today’s situation in Fairfield echoes that at the Stoneridge Farm in late 2018 and early 2019 that resulted in a moratorium on land application of biosolids until test results could show that products would not cause increases in levels of PFOA, PFOS, and/or PFBS above Maine’s conservative, risk-based screening values of 2.5, 5.2, and 1900 ppb. (These are the only formal biosolids/residuals screening levels in the nation.) Numerous facilities, including Lewiston-Auburn, were seriously impacted by the new limits and incurred major cost increases for taking their residuals to landfill. That case was highlighted in the 2020 report by CDM Smith titled “Cost Analysis of the Impacts on Municipal Utilities and Biosolids Management to Address PFAS Contamination” Since then, other communities like Oxford, are planning to end their long-standing recycling program and instead dry and landfill their wastewater solids [see Oxford’s Sewer Department eyes new route for waste processing - Lewiston Sun Journal] Next door, after decades of land applying liquid Class B biosolids to local farmland, Mechanic Falls (a longtime NEBRA member) is now transporting its solids to another wastewater facility. Initial testing at the Mechanic Falls land application sites found typical low levels of PFAS, indicating that even decades of application of municipal biosolids that are not impacted by large industrial inputs cause minimal impacts.

Testing in Maine and around the country have found PFAS at measurable levels in pretty much every biosolids. Typical levels of the PFAS most focused on - PFOA and PFOS – are in the low 10s of parts per billion (ppb). A ppb is equivalent to one second in 32 years. Where they have been tested, including at many farms in Maine that received typical, non-industrially-impacted biosolids, soils show PFOA and PFOS in the single to teens ppb.

There appears to be a clear distinction between typical municipal biosolids with low levels of PFAS that come from the myriad consumer products that contain them and the relatively rare situations where municipal biosolids are contaminated because of major industrial inputs of PFAS from industries upstream. In Maine, the industry of concern seems to have been some paper products manufacturers who used large volumes of PFAS coatings. But this is not certain; investigations are ongoing. And this does not implicate all paper producers; testing of residuals from many paper mills has found only low or very low levels of PFAS (when compared to typical municipal biosolids).

In other states, the industrial sources of PFAS are different: in Michigan it’s metal plating, in North Carolina it’s carpet manufacturing. When these industries discharge to a municipal wastewater facility, the biosolids are industrially-impacted. As in Maine, further investigations will find additional municipal biosolids land application sites that have elevated soil levels where the biosolids were industrially impacted. But, as in Maine, the large majority of municipal biosolids land applications likely do not elevate soil and farm levels significantly.

But the significance of even low levels of PFAS in soils and farm systems is still being debated. This year, Maine legislators overwhelmingly approved adoption of one of the nation’s lowest drinking water (and groundwater) standards in the world: 20 ppt (parts per trillion; 1 second in 31,700 years) for six PFAS combined, mimicking the Massachusetts standard. There are potentially many situations where modern human activities are impacting groundwater at close to those very low levels. A study on Cape Cod, where the only known PFAS sources were home septic systems, found the sum of PFAS in home drinking water wells at levels approaching 20 ppt. And several rural New England school wells have been shown to be impacted by their own septic systems at levels well above 20 ppt; for decades, those schools were cleaned and waxed daily with PFAS-containing products.

With its very low regulatory standards, will Maine require costly remediation of myriad soils with minimally elevated levels of PFAS from typical, non-industrially-impacted biosolids land application and other activities? That question remains unanswered, as research continues. Maine CDC is looking closely at plant uptake of PFOS in particular, because PFOS seems to be the most bioaccumulative in dairy and cattle operations. Preliminary findings suggest that grasses – hay used for animal feed – take up some PFOS (and other PFAS), which may lead to elevated levels in cows and cattle. In contrast, corn does not appear to take up PFOS at any significant level. So, in the short-term, mitigating PFAS concerns may be possible with adjustments in feeding – a small glimmer of hope for those few farms that are dealing with industrially-contaminated soils.

But there is no question that, for those few Maine farms, the discovery of industrial-level PFAS contamination is devastating, because, whether the Maine standards are reasonable or excessive, they are what they are, and they mean the end to these farms’ operations in the near-term and significant mitigation and changes over the longer-term. Maine’s legislature, agriculture department, and other agencies are aware of these sad situations and are working to help with funding and mitigation support. And there is a chance the federal U. S. Department of Agriculture programs of support for contamination issues at farms can be further sources of financial support. For example, the Dairy Indemnity Payment Program (DIPP) now includes PFAS as one form of contamination that is eligible for compensation; it has been used at a New Mexico dairy that was widely reported as having large PFAS contamination from a neighboring military base and its use of fire-fighting foam.

Back in Maine, most recently, on December 14th, the Portland Press Herald and others reported that PFAS had been found in the eggs of chickens of Fairfield area families with contaminated water (see: Forever chemicals found in chicken eggs as Maine expands testing to 34 communities - Portland Press Herald). Where water filtration systems have already been installed, PFAS concentrations in chicken egg yolks has gone down since late 2020. The State subsequently found that PFAS spiked again in free range chickens. The soils in these situations has been sampled, and testing results are expected at the end of January. According to the Press Herald, “state toxicologist Dr. Andy Smith said people shouldn’t overreact to the news of contaminated eggs or worry about the egg supply. Nor should people think that PFAS chemicals are in all communities, gardens and livestock. ‘Everywhere we’ve worked so far are places where this is a known source that’s resulted in water that’s fairly high’ in contamination, Smith said. ‘By far, the first concern is the water exposure to the people drinking the water, and the other exposure pathways are secondary to those.’”

Maine agencies are now moving ahead with testing of all farms where biosolids and other residuals have been applied in the past – some 500 in all. The legislature appropriated $30 million in funding for PFAS mitigation work, which includes 19 new staff just hired to do this work. The State has identified 33 sites in addition to Fairfield as potential hot spots for PFAS. These “Tier 1” sites will be tested first. Much has already been spent on installing filters for the nearly 200 private drinking wells that were impacted in the Fairfield area, and that work also continues. Maine has also been out in front with recent legislation to reduce the sources of PFAS, but these laws come too late for biosolids and other residuals that were processed and land applied in the past. NEBRA Reg-Leg Committee Chair Jeff McBurnie, from Maine, told NEBRAMail “The more the State expands testing, the more likely it is they will find another Fairfield but let’s hope not. Fairfield seems to be a real anomaly with much higher levels than are being found at other sites according to the data posted by the Maine DEP.”

To help pay to address PFAS concerns, one part of the Maine Legislature’s 2021 PFAS action is a $10/ton fee for “handling” of sludge or septage. The new law, which became effective October 18, 2021, requires Maine DEP to create a “Land Application Contaminant Monitoring Fund.” According to a November 10th Maine DEP memo to biosolids stakeholders, the new fund will be "used by the Department for the testing and monitoring ‘of soil and groundwater for PFAS and other contaminants and for other related activities, including, but not limited to, abating or mitigating identified contamination and the effects of such contamination through the provision of access to safe drinking water, the installation of filter treatment systems or other actions.’” The DEP expects that the first payment of the new fee will be required in early 2023, when data on solids generation and handling in 2022 are available. In the meantime, starting soon, Maine DEP will initiate rulemaking related to the new fee, and there will be opportunities for stakeholder input. One question that Maine DEP has raised already is about where in the chain of solids management steps will the fee be imposed, which relates to who, exactly, will be paying the fee. A copy of the Maine DEP letter is available here: State actions & key documents — NEBRA (nebiosolids.org)

NEBRA continues to provide PFAS-related materials for its members, including updated fact sheets for communicating with farmers (Resources: Key Topics of Interest — NEBRA (nebiosolids.org). NEBRA is planning a training webinar regarding open and honest communications with farmers and other stakeholders about this very difficult topic, with so many unanswered questions still. NEBRA is also involved in the University of Maine’s George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions Project titled “Integrated assessment of alternative management strategies for PFAS-contaminated wastewater residuals,” which received funding from the U.S. Geological Survey.

The references below provide further information, including the perspective of IATP, a group that has long opposed the use of biosolids and is paying close attention to the situation in Maine.

References

IATP - Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy: Forever Chemicals and Agriculture Case Study, November 2021, a report that lays out the perspective of a group long opposed to biosolids use who make generalizations from the few farm situations of industrially-impacted biosolids impacts. https://www.iatp.org/documents/forever-chemicals-and-agriculture-case-study

Other IATP coverage:

https://www.iatp.org/https%3A/www.iatp.org/special-issues

https://www.iatp.org/will-epas-forever-chemical-plan-leave-farmers-behind

PFAS in deer meat:

PFAS in eggs & most current situation:

Other:

dmc_dipp_crp_mal_lpd_off_program_final_rule.pdf

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40726-020-00168-y